Place-Based Memory

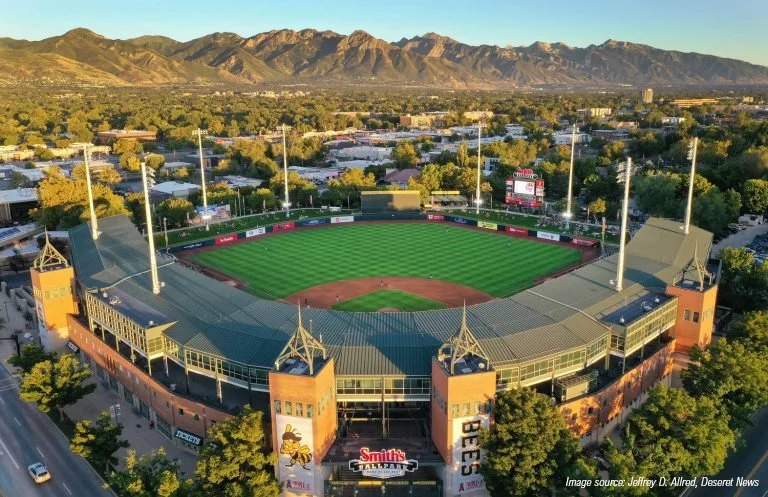

The best view in baseball

Source: Scott Sommerdorf, The Salt Lake Tribune

Place-Based Memory is a Regenerative Design principle outlined in the study, Living Community Patterns: Exploratory Strategies for a Sustainable San Francisco (2015). Throughout this post, regenerative design principles from that document are highlighted like this.

A regenerative design opportunity has presented itself in Salt Lake City’s (SLC) Ballpark Neighborhood. For the first time in 99 years, this particular spot will no longer be the designated home of its namesake, the national pastime, an important civic function, and a one-of-a-kind community asset that has differentiated Ballpark from all other parts of SLC.

The decision to move our minor league baseball stadium to make room for a potential major league baseball (MLB) team is one that I have mixed feelings about, but that is tangential to this post. Instead of debating the matter, I want to memorialize some of my experiences in what for me and four generations of my family is a special PLACE, describe some of the site history as I understand it, and encourage those change agents who are privileged enough to be involved in the replacement projects that are now in progress to plan, design, build, and operate mindfully (in both the historic and new locations of the contemplated stadiums).

This is a personal research effort that turned into a thought experiment. It is not a critique of any company or firm. So, let’s step forward into the near future to imagine how things could be, and then walk back in time as we remember and relearn from the way things were.

The Future of the Ballpark

2031

The Ballpark Neighborhood has been fully reinvigorated using the Pattern Language of Living Communities. Life settles in, and PLACE re-forms. Hope has blossomed here.

At the base of one of the two preserved masonry spire towers, a bronze plaque that is rarely read by passersby tells parts of the following story…

2030

A new mixed-use development that includes the old ballpark footprint and its adjacent parking lots achieves ILFI Zero Energy certification, having generated more energy on-site than it consumed over the course of 2029, realizing the promise of the 2030 Challenge. What didn’t seem possible at this scale happens through a thoughtful combination of existing technologies that will pay for themselves before 2050, becoming revenue generators for cyclic reinvestment back into the neighborhood thereafter. Critical to this successful outcome was a Footprint Analysis that helped to scale the development to a level that was within the natural carrying capacity of the location.

2029

Plant managers and building operators tune and optimize neighborhood utility plants and individual building systems. The composting building gets an RDA grant for its garden roof (Roof as Resource) and the park on top is opened to the public. A couple has their wedding pictures taken under the solar panel canopy that shades part of the park. Hope is branching out.

2028

Buildings begin to open in this new Human-Scaled Community. Work spaces are set up on the ground floor and living spaces are made into homes on the upper floors. Food vendors open for the day around The Infield, a food truck plaza that draws in office workers and residents from all around the Ballpark Neighborhood (and beyond). Shop owners arrange their wares inside their stores and out on their sidewalks. People are working hard to make it work here.

2027

The miracle of construction unfolds. See in your mind’s eye time-lapse satellite imagery of ant-like equipment moving about a muddy site while the vision of planning and design teams incrementally takes shape. Gradually the mud and dirt subsides and Blue-Green Streets emerge along with Rewilded landscapes. Anticipation becomes excitement. Ideas are made real. Hope takes root.

2026

A 32-year-old civic structure is deconstructed, not demolished. The existing building materials are seen as useful resources, not waste destined for landfill, so they are removed in a manner that promotes reuse and recycling. Seats are removed and reinstalled in the ‘Old Timers’ seating section at Daybreak Field, a Show & Tell story that gets repeated often. Vertical brick is panelized as cladding for a private commercial project downtown. Block is crushed and used as aggregate in a public works paving project in the neighborhood. Metal roofing is reused on a Place Collaborative project for a non-profit organization in Cody, Wyoming. Structural steel is recycled, its molecules redistributed throughout Western US. Critically, two of the brick spire towers are preserved as a Place-Based Memory, meaningfully planned into in the new mixed-use development that is to come: one will be a publicly accessible observation tower and the other will house neighborhood-scale utility infrastructure.

The ballpark has four ‘spires’ – masonry stair & elevator towers topped with a steel abstraction referencing an iconic local landmark.

Source: Jeffrey D. Allred, Deseret News

2025

The Regenerative Plan for the Ballpark Neighborhood is complete. It calls for a Living Community and plans for a Second Act for portions of the stadium. The plan is fundamentally different from anything else that has been made or remade in the Intermountain West because of the way it internalizes its responsibility for energy and water resources. Rainwater collection policy and regulation are improved in order to make this possible. The plan also calls for meaningful material reuse at Daybreak Field – one of the four existing green steel spires is to become a shade pavilion in the outfield there. Another is being salvaged and stored for reuse at the MLB expansion stadium that was just announced, linking both new stadiums to the old one. And having been involved in a SEED planning process, the Ballpark Community Council whole-heartedly endorses the Plan. The seed of hope is now planted.

A Look Back at Memories of the Ballpark

2024

We go to the last game, a day game, at this special PLACE on Sunday September 22. Looking at the building with an architect’s eyes, I cannot see what is lacking, what is worn out, or what is failing. If the business of baseball is unsuccessful in this location, it is no fault of the facility. I also can’t see why the neighborhood has been blamed – the development opportunity of the vast surface parking lot just north of the ballfield has been unrealized since I first came here as a kid in the 70’s. It is a lack of imagination that leads to this result, I realize.

2023

We attend a night game, the deepening twilight sky contrasted against the alternating green-green of the mow-striped grass under the lights is stunning. We’ve been here so many times. So many I can’t count them. We used to sit on the third-base side from time to time, but I can’t remember why (until I write another section of this post).

June 10, 2023 “The thrill of the grass…”, Shoeless Joe Jackson in Field of Dreams

2015

One of my business partners organizes a company party at the ballpark. A distant storm looms over the Great Salt Lake. She and I watch it from the outfield walk as a salt-stung wind kicks up and the sky darkens. It’s a sublime Something Wicked This Way Comes kind of a moment. A rain delay is called, tarps are rolled out over the infield. A late summer monsoon steamrolls over us. People move onto the main concourse for cover, the rain pouring off the upper deck, along with my hope for the party. The uncommitted head for their cars with only soggy programs for umbrellas. The game is eventually cancelled. At this point, I’m finally willing to leave.

2014

The stadium is renamed (again), this time to Smith’s Ballpark. The corporate branding of buildings is interesting in the pejorative sense. Appropriately, the Red Sox play in Fenway Park, named for PLACE (which naturally endures) rather than corporations (which come and go). I do applaud the effort to put location first in the name of Daybreak Field.

Pre-game photo taken September 8, 2024 - Fenway is the oldest active ballpark in Major League Baseball. It is a temple to the game, and I hope it is a model, inside and out, for the MLB stadium SLC may be getting in the near future.

2011

We take the kids and a close family friend to see a game on our local Founder’s Day. They are excited to take a blanket out onto the field to watch fireworks after the game. We sit on the third-base side because of ticket availability for a larger group coupled with a spontaneous decision to go. The PLACE is so packed, just like it’s supposed to be.

Photo taken July 24, 2011

This is community to me – being together with both family and strangers living a shared experience. This is why it is so easy to talk to folks in a ballpark, or on a hiking trail – if nothing else, you know you have this one thing in common.

2009

We take my dad to a game on his birthday, May 29. Born in 1934, he is now 75 years old. We sit in one of the best seats in the park (though there are no bad seats in this park) – an accessible spot for his wheelchair at the edge of the main concourse behind the home team (first base) dugout. He tells us stories of when he came here as a kid, and the night the grandstand burned down. We eat hot dogs of the Chicago persuasion, being Cubs fans and Salt Lake having no defining cuisine of its own. I do not know that this will be his last trip to the ballpark.

2004

Our kids run the bases after the game. We ask our oldest (6) to watch after their sibling (4) as they go out onto the grass toward home plate with a gaggle of other kids. Our oldest of course gets caught up in the moment and bolts for first base, cutting the corners to save time. At three feet tall with no stride to speak of, we’re scared our youngest won’t make it to second. But they are fearless. The stands cheer for them and chant their name with us as they reach and round third, the caboose of the train of youth circling these bases. Grandpa is greatly moved. He is a great old railroader. He cries at this moment, decades in the making.

1996

I graduate with my master’s degree in Architecture in May, the same month that my dad retires after working for the Union Pacific Railroad for 44 years. We naturally go to a ballgame to celebrate. One of our players, an up and coming third-basemen named Todd Walker, has an incredible game. He has a superfan a few rows in front of us near the edge of the field who keeps calling to Walker after he hits homer or makes a barehand play to first base. The folks in the stands roar when the fan haltingly professes his love after Walker makes a diving catch on a scorching line drive down the baseline – “TODD – WALKER – YOU – ARE – SO – SO – SO – GOOD!”. Walker turns and tips his hat, like it’s 1926 instead of 1996. The superfan flops down in his chair, exhausted from the extasy of the interaction. I tell my wife if he smokes a cigarette the story will be complete.

1994

The new stadium is complete and getting ready to open in the spring. It’s called Franklin Quest Field (named for the day-planner company that is based in SLC). One of my classmates works with the architect who led the team that made this beautiful PLACE. She gets us a tour, and he tells us that the circulation is based on the work he did at Camden Yard in Baltimore. Hats off and hand over your heart, someone just said Camden Yard for cryin’ out loud. He mentions that the baseball-green spires on the vertical circulation towers are a nod to the iconic Salt Lake Temple. All the architecture students silently nod in reverent agreement and understanding of Place-Based Memory.

1993

Derks Field is not thoughtfully deconstructed, but destroyed by hook and by crook, down to the sentiment of the name. The demolition of the concrete grandstand is complete, and a poignant article is written. I have a hard copy of this article, thanks to my thoughtful in-laws who work for the newspaper (the thing before the Internet). And that’s all I have to say about that.

1990

I go to a State 5A playoff game at Derks Field with my high school buddies. We get the day off of school for this, because even the principal and teachers know that this is the most important thing we could be doing right now. We feel like we’re in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, going to a day-game at Wrigley. I do have a bright red car with an Italian sounding name (Corolla). It’s sunny day in May, so my Danish complexion gets a bit of sunburn. And we talk about girls. Hey batta batta, sawing batta!

1983:

It’s so hot, and it’s only May. And it snowed so much the last few years – snowbanks higher than my brother’s 220 skis. There’s flooding all over the city (not the kind of Blue-Green Streets we’re looking for!). My best friend’s mom gives us a reward for filling sandbags with her at the park – a trip to Derks Field. We park on the opposite side of the river that is State Street so that we can experience the temporary bridge that has been built over it. From above, I see trout swimming in the shade of the bridge, pacing side-to-side over static yellow pavement markings. At the game, I buy a Salt Lake Gulls pennant for my bedroom. Friends from Pittsburgh and Philadelphia join it over time. They stay pinned up on the wall, gathering a patina of second-hand smoke, for two decades.

1979:

For the first time in my young life, I go to a baseball game that I’m not playing in. My best friend’s mom and dad coach the baseball team that he and I play on. They are so good at organizing a bunch of seven-year-olds. I learn important fundamentals from them. We get a treat at 7-11 after every game, whether we win or lose. And they take us to Derks Field to celebrate that we made the Taylorsville Pee-Wee All-Star Team. I can’t believe how big the stadium is, or why trough urinals exist. All I want to do is play and watch baseball. I haven’t seen enough summers to remember or know that this summer will end.

Derks Field entrance gate in the 1970’s, unchanged except for some orange paint (very on trend for the era).

Source: Alchetron, digitalballparks.com

Going Back in Time through the Ballpark’s History

1958

Derks Field is expanded to 10,000 seats, and remains community-owned.

Today’s ballpark is privately owned and has almost 15,000 seats, though it’s record attendance pushed up to 17,000 one year (2000) thanks to the lawn seating in the outfield. Fenway has 38,000 seats, but magically feels just as intimate as our minor league ballpark. Dodger stadium has three decks, and reaches 56,000 seats (while beautiful, it is dizzying and alienating). Wembley Stadium? 90,000 seats. I have got to see a match or concert there…

Tomorrow’s ballpark will, once again, not be community-owned. How much seating will there be at Daybreak Field? A paltry 6,500 (what is this, 1947?). We don’t want to cut off our MLB expansion chances, I suppose.

1947

[must be read in an old timey radio sportscaster’s voice] The battlin’ Bees will return to the Hive tonight for their belated Pioneer League opening with 4000 bleacherites on hand and no carriage trade to bid them welcome. Temporary bleachers alongside the foul lines will accommodate the patrons due to the fact that the Derks Field grandstand isn’t ready yet. – Deseret News

So it turns out that construction schedules are still the same – a little longer than expected. The building was rebuilt in concrete so as to eliminate the risk of another loss to fire. Not much to look at from the outside, but the sign uses a nice font that will pass the test of time. And what’s up with that terrifyingly cantilevered press box? Even before I had an architectural education, I knew that was off.

It’s a geode, Dean Bill Miller would have said – not much to look at on the outside, but on the inside you will find something special… The Derks Field entrance gate in 1948.

Source: Salt Lake Tribune

1946

September 25 - Derks Field, home of the Salt Lake Bees of the Pioneer baseball league, was all but destroyed…by a fire which started in the empty grandstand. – Lewiston Morning Tribune

September 30 - A 32-year-old Salt Lake man confessed early today to setting Derks Field grandstand afire last Tuesday “with a cardboard carton full of papers,” and to lighting five haystack fires in Salt Lake County since July 31. – Deseret News

Source: Salt Lake Tribune

These articles and image confirm the stories my father told me. On the night of the fire, the glow from the flames could be seen from his house a few blocks northeast on Lowell Avenue. It was devastating to the community that owned the park and the ball club, and to his group of friends that would walk to the ballpark. In my imagination, that’s my grandma and her new husband, the polite policeman that courted her into a second marriage, on the right-hand side.

1940

…Derks was, as Salt Lake Tribune contemporary John Mooney remembers, "A little round man who smoked a cigar and everybody liked."

Early during the ensuing 1940 season, the Pioneer League Baseball Writers, led by a trio of Salt Lake writers - Mooney of the Tribune, Dee Chipman of the Deseret News and Al Warden of the Ogden Standard Examiner, organized a baseball benefit game at the Salt Lake ballpark, which was known at the time as Community Park.

From some of the proceeds of that game - an exhibition between the Harlem Globetrotters baseball team and the House of David baseball team - the writers talked the city commissioners into buying a plaque and re-naming the ballpark Derks Field. Ceremonies were scheduled for a home game later in the summer, during the height of the baseball season.

"An ambulance picked up Mr. Derks at his rest home that night and drove him to the ballpark," recalls Mooney, who recently retired as the Tribune's sports editor. "He couldn't talk, but he waved to the crowd and they gave him a standing ovation. He was greatly moved. He was a great old gentleman. The park became his tribute."

When he died four years later, it became his memorial. – Deseret News

1928

After the stand was removed and erected, and the Utah-Idaho League got under way again, the community corporation deeded the entire property to Salt Lake City without charge…. The plant and ground were rapidly put in shape for the 1928 baseball season. We had to use some of the gate receipts to pay bills, and the San Francisco Baseball Club…gave us additional funds to meet the operating costs. – Deseret News

1925

In the autumn of 1925, Pat Goggin, George Relf, the late John C. Derks and the writer [Les Goates] drove to West Temple St. and Thirteenth South St., and measured off a huge vacant lot, as a possible site for a baseball park. The following winter and spring the big grandstand at historic Bonneville Park, Main and Ninth South St., was moved down there by a group of civic-minded citizens and became Community Park, one of the most spacious and attractive baseball plants in all the minor leagues. – Deseret News

1915

The first location for baseball in Salt Lake City was called Bonneville Baseball Park at the Salt Palace, a fairground of sorts, a little north of the current ballpark. That lot was the downtown Sears my whole life. It’s a vacant lot today, but with an incredible taco cart the last time I checked. And it may yet become a hospital, or something else if that deal falls through. Point is, I won’t ever forget what it was – now that I know.

Source: KSL

It turns out that now is not the first time that our ballpark (or an event space called the Salt Palace for that matter) has moved. Bonneville Baseball Park was located on 900 South before its grandstand was moved to 1300 South. Everything old is new again, if we will but try.

The Take-Home Message

(to use a now nostalgic turn of phrase from a beloved mentor, Tim Thomas) is this:

“Several rules of stadium building should be carved on every owner's forehead.

Old, if properly refurbished, is always better than new.

Smaller is better than bigger.

Open is better than closed.

Near beats far.

Silent visual effects are better than loud ones.

Eye pollution hurts attendance.

Inside should look as good as outside.

Dome stadiums are criminal."

- Sportswriter Thomas Boswell in Baseball Digest (August 1979, Certain Ballparks Have Their Own Special Charm, Page 67)