Healthy Building Material Chemistry

Architects get to do a little bit of everything in their job, and sometimes we must dive in deep to research something we are unfamiliar with. Here at Place Collaborative, we specialize in sustainable and regenerative building design. In doing so, our work is to design everything to be in harmony with a healthy environment. During the design process, our considerations range everywhere from the assembly of the entire building envelope down to the molecules that make up individual building materials. Obviously, the building is important. We often think about major elements like walls, roofs, floors, plumbing, electrical.... but why would we care so much about the chemicals that make up the building products?

Why are Material ingredients Important?

It’s important to consider chemicals used in building materials for several reasons:

The wellbeing of the building’s occupants.

The wellbeing of the workers who construct the building.

The wellbeing of the workers who make the product.

The maintenance of a healthy ecosystem.

Products used in buildings can affect any number of those things. Have you ever gone inside a new building or remodel, and it smelled like chemicals or “new car smell” and you or people around you got headaches or nose or throat symptoms? Those are just a few symptoms that come from exposure to volatile organic compounds (VOCs) according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). But it’s not just VOCs that can cause health issues. Over the years, we’ve seen several chemical products banned from buildings due to dangerous health effects. Lead paint and asbestos might sound familiar. But what about the chemicals in building products that are bad for us that haven’t been banned yet? That’s where it comes in handy to know how to find healthy products. You have to know a little chemistry, but you don’t have to be a chemist to do it!

Introduction to Material Vetting

Our Collaborators have worked on a number of Living Building Challenge (LBC) projects. LBC is a building certification that has been achieved by some of the most sustainable buildings in the world. The creators of LBC, the International Living Future Institute (ILFI), have composed a list of harmful chemicals called the “Red List”. Finding and eliminating products with red-listed ingredients is one of the most challenging aspects of the Living Building Challenge but understanding how to read and find the chemicals is not difficult once you learn the basics.

Front page of a Health Product Declaration

So, let’s start with a Health Product Declaration (HPD) sheet that you would get from a manufacturer. These can be found on manufacturer websites but there are also databases like Mindful Materials or ILFI’s Declare database that make it easy to search for product information. An HPD has a list of chemical ingredients with data about the chemical. On the left-hand side is the name of the ingredient. Sometimes chemicals can be listed using their IUPAC name which can look intimidating; this nomenclature is used to help scientists to categorize chemicals despite the complexity of their structures. The nomenclature technicalities would require an entirely separate blog post, but you can see IUPAC’s published guides if you are curious.

Material Vetting Process

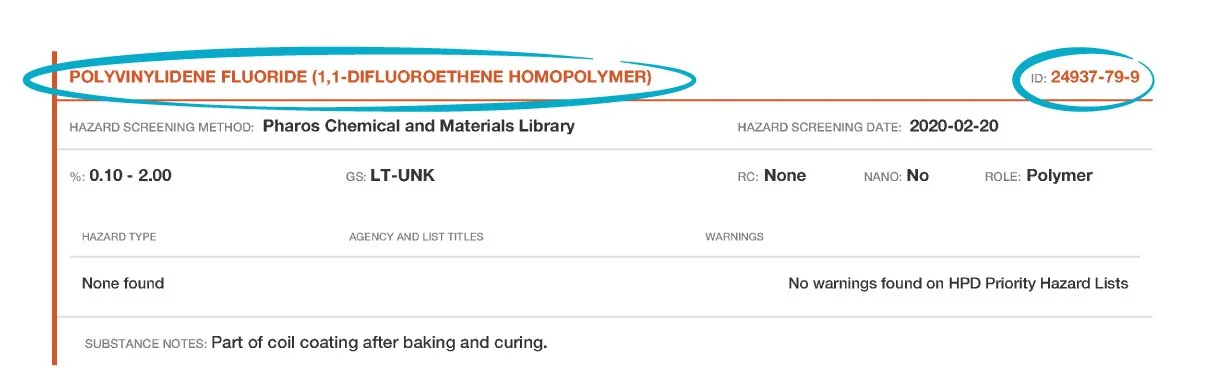

Below is a chemical you might find on a Health Product Declaration (HPD) sheet. Here it is listed with both versions of its name. Its common name: Polyvinylidene Fluoride and its IUPAC name: 1,1-Diflurooethene homopolymer.

On the right, lists its ID also known as its CAS number. The CAS number is key to searching the Red List since the Red List only contains one form of the chemical’s name, making it harder to search for the chemical by name. The CAS number is attached to all versions of the name and is therefore the most reliable searchable component.

Using the CAS number, all you need to do is run a search for it on the Red List. This chemical is on the Red List, so the product would disqualify from being deemed “Red List free”.

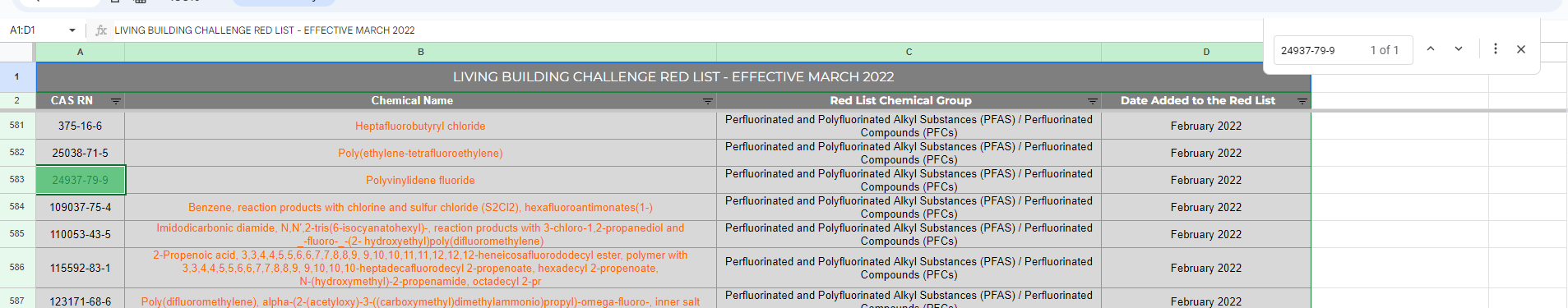

Using the search function, you can search the Red List for the CAS number in question

Simplifying the Red List

You might be thinking, the Red List is so long and there are so many chemicals, how can I quickly know which ones are bad or what if I don’t have a CAS number?

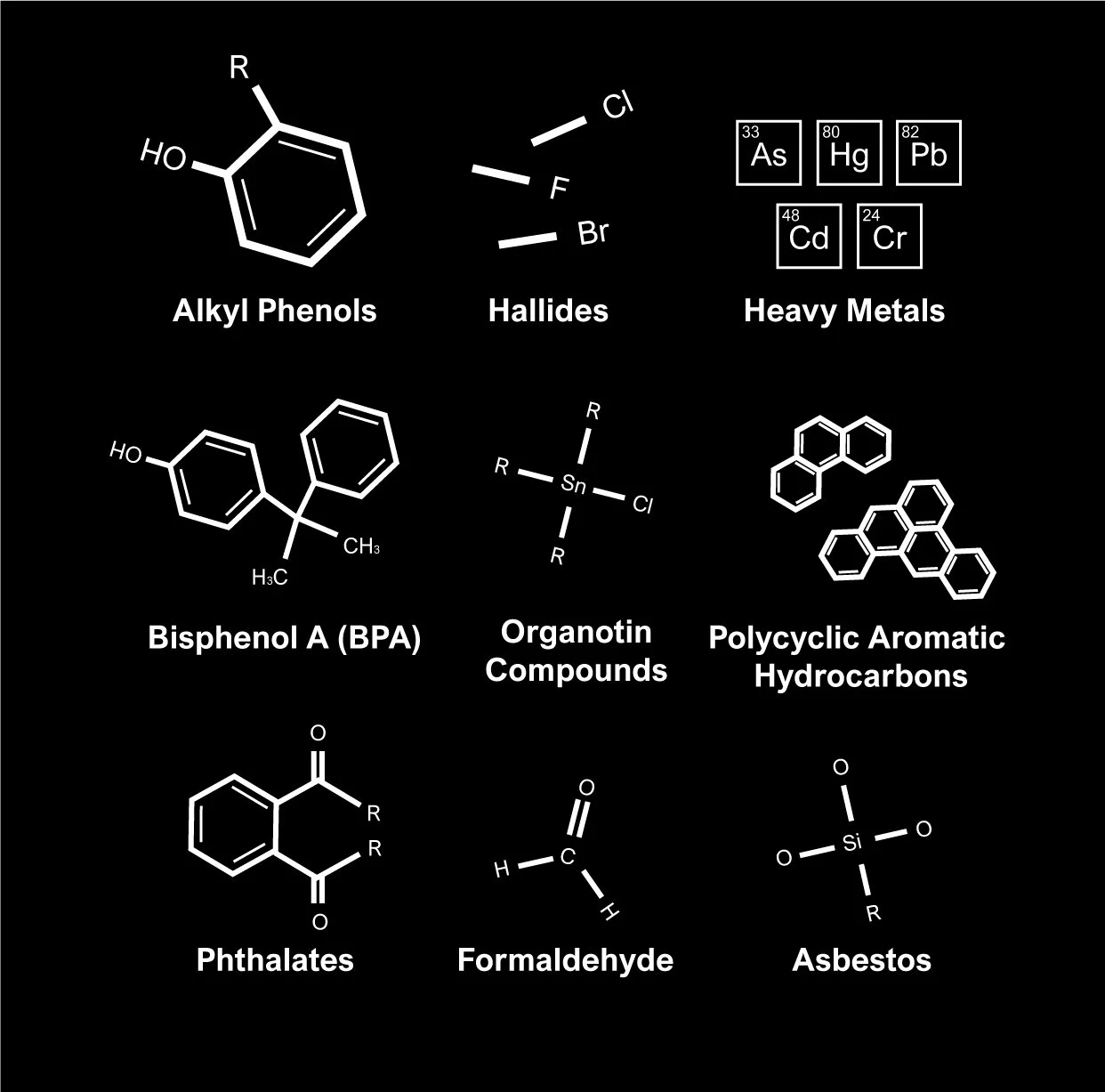

While we don’t have a perfectly accurate test, we do have some general guidelines we follow in our Red List process. We Google the molecular structure of the chemical in question. Organic chemicals have defining “groups” that provide a set of characteristics to those types of chemicals. If a molecule contains one of the groups below, it is likely (but not always) a Red List chemical.

Chemical groups that may indicate a Red List material

These chemical groups also show up in the names. If you see “bromo”, “fluoro”, “chloro”, “phenol”, or names of substances you already know are harmful like formaldehyde or asbestos. In addition to this post, our Open Source page now has a cheat sheet guide with molecular structures and names to look for when you are trying to eliminate Red List chemicals.

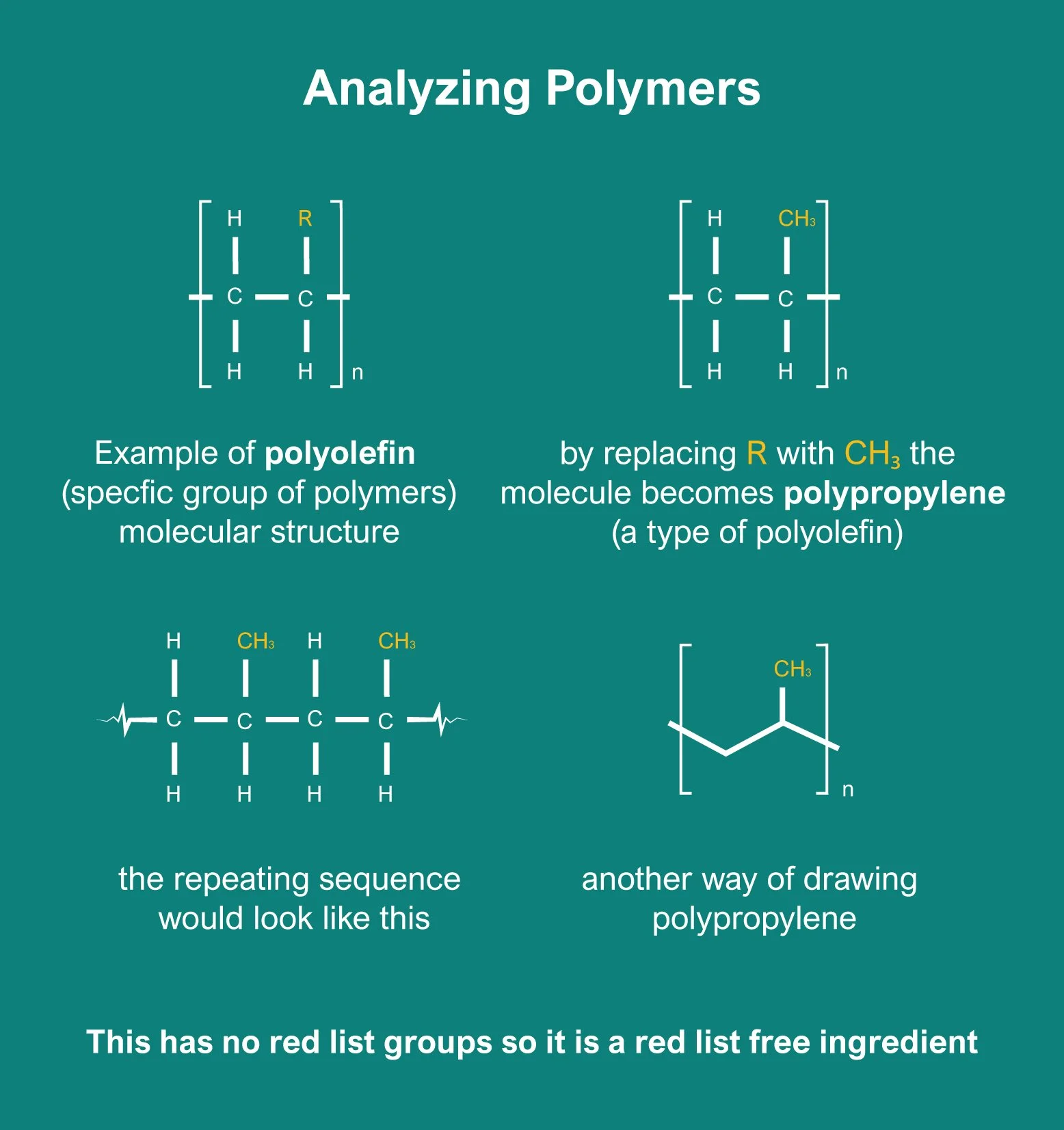

Sometimes, Polymer groups are written in shorthand using brackets around the molecular group. That means, this portion of the molecule is repeated in a chain ‘n’ number of times. The letter ‘R’ is used to indicate an attached carbon chain, usually ‘R’ will be defined as a group.

These are the basic principles surrounding Red List Chemistry. Now you are ready to begin material analysis to ensure a healthy building!